Recently there has been a series of news articles and opinion pieces casting doubt on the long-held belief that seeking a college degree is a key step toward the American Dream of a more secure and prosperous future. When College Possible was founded 18 years ago, almost no one questioned the idea that supporting low-income students on their college journeys was a good idea. Indeed, most people reflexively and enthusiastically agreed that America would be better, stronger and fairer if more low-income students got a chance to go to college. The basic idea of College Possible rarely required much explanation or justification. It seemed to be an obviously good thing to do.

But in recent years, and especially in the last 18 months, we have witnessed a powerful and unsettling shift in the public’s view of college. The growing skepticism of higher education isn’t just a partisan issue. According to a recent paper released by Results for America, “only 49 percent of Americans believe that earning a four-year degree will lead to a good job and higher lifetime earnings. Skepticism is particularly strong in white working-class voters, among whom a majority — 57 percent — believe that a college degree ‘would result in more debt and little likelihood of landing a good job.’ ” And a Pew survey from July 2017 caught many education leaders by surprise when it reported similar findings.

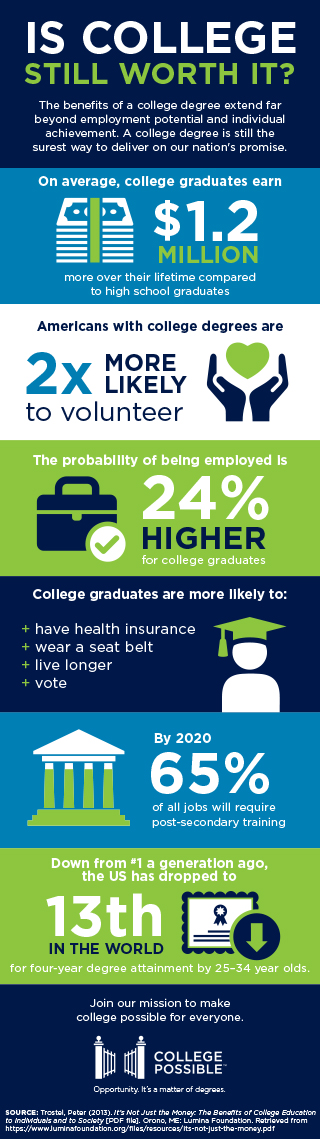

It’s tempting to dismiss these views by pointing to the overwhelming evidence that earning a college degree is still the surest possible pathway out of poverty and into the middle class. Almost all the job and wage growth now goes to people with some form of post-secondary education. Indeed, many studies show that a four-year college graduate will earn between $500,000 and $1.2 million more over their lifetime than a high school graduate. During the Great Recession unemployment for high school graduates was substantially higher than it was for college graduates, and during the ensuing recovery virtually all of the new jobs went to college graduates.

It’s easy, then, to conclude that college is still a “no-brainer,” right? Well, it’s actually more complicated than that. Those of us who advocate for increased college degree attainment, especially for low-income students, need to acknowledge a range of disturbing facts.

First, only 55 percent of students who began college in the fall of 2010 earned a degree or certificate within six years at either their original college or after transferring. This means nearly half of all students who start college fail to earn a degree. And the results for low-income students are even worse: less than a third who start college will ultimately earn a degree or certificate.

Second, U.S. student loan debt now totals $1.3 trillion, more than the total for either credit card or car debt. Indeed, the average student loan debt load has now reach more than $37,000. As a nation, we are approaching a tipping point where the average student loan debt will not be sustainable given average entry level salaries. In 2016, 1.1 million students defaulted on their loans. Once again, the situation is even worse for low-income and under-represented students who disproportionately leave without a degree and the increased earning potential it provides. These students default on their loans at an alarming and unsustainable rate.

Given these factors, is college still worth it? The answer is still “yes,” and a resounding “yes” for low-income students. Here are just a few reasons to believe in the value of a college degree:

- Higher salaries, employment rates and greater job satisfaction.

- Better health outcomes and greater life expectancy.

- Greater job safety. The incidence of receiving workers’ compensation is 2.4 times lower.

- Better citizenship. Those with college degrees are more than twice as likely to volunteer.

- Stronger economies and communities. In part due to increased income from taxes, but there is also a direct correlation between an increase in a community’s college-educated population and income growth for workers of all education levels.

[/photo_left]These factors, and many others, translate into more vibrant communities and a stronger country. This not only helps America compete with the rest of the world, but perhaps most importantly it helps us reach our full potential as a nation.

[/photo_left]These factors, and many others, translate into more vibrant communities and a stronger country. This not only helps America compete with the rest of the world, but perhaps most importantly it helps us reach our full potential as a nation.

But like most things, with this reward comes risk, and many students — low-income students in particular — are not educated in the best ways to select a college. Research has shown that students do best when they enroll in the best schools that accept them. Far too many low-income students fail to consider a four-year college, or a more selective college and instead “undermatch” by attending a less demanding school, usually with much lower graduation rates.

Cost is also a risk factor, and with the rising cost of tuition, a majority of students will need to take out some type of loan. A good rule of thumb is to avoid taking on more total student loan debt for a four-year degree than one expects to earn annually after graduation. But assessing the total cost of college can be difficult to do since so many colleges offer “discounts” on their publicly stated tuition that are poorly communicated to the public.

All of these risks are especially true for low-income students, who often don’t have parents with experience in the process of going to college, typically attend high schools with too few guidance counselors and are left without anyone to help them navigate these challenges. Over the last two decades, an array of nonprofit organizations have formed to help coach students through these (and other) hurdles, including the organization I founded, College Possible. Some of these organizations have demonstrated significant and measureable results, but they reach only a tiny fraction of the students who need and deserve their help. Our nation will need to invest more resources targeted to help low-income students and their families manage these increasingly complicated questions and challenges.

Overall, these shifts in public opinion do have some basis in reality, as I’ve noted, but they stand to hurt low-income income students the most, because these students have fewer examples of college success in their own lives. By comparison, almost all upper middle class families send their own kids to college. Students from the upper quarter of the income distribution are now five times more likely to earn a degree within six years of high school graduation than students from the bottom quarter. As Richard Reeves notes in his book, “Dream Hoarders,” almost all of the gains in income and wealth over the last several decades have gone to those in the upper 20 percent of the income spectrum. Their children, even in the face of this shift in public opinion, and despite political affiliation, go to college at extraordinarily high rates. It’s the rest of our students we need to worry about.

The biggest risk of this emerging view that “college is not worth it” is that many students and families from the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution will come to believe it and stop striving to earn a college degree. Adopting the “college is not worth it” view will leave them ill-equipped to compete in an increasingly global economy, without the skills needed for good paying jobs and ultimately with little hope to have a better life than their parents. And this won’t just hurt these students, it will also make us weaker and poorer as country. Perhaps most disheartening, if this idea continues to take hold and becomes the conventional wisdom, it may finally break our nation’s most essential promise that if you work hard, sacrifice and delay gratification, you can earn a ticket to the American Dream. At College Possible, we invite all citizens, and especially advocates of low-income students, to help us address and reverse this emerging trend before it’s too late.